Roof Beam Reader

Adam Burgess

August, #TheSealeyChallenge, and More

Posted on September 3, 2020 by Adam Burgess

Hello, my beloveds. Long time no see! My apologies for the absence. I’m sure many of you, like me, have been struggling with the continued pandemic, the back-to-school season, and the rather horrifying events taking place around the United States and the world, not least of which are the incidents in Portland and Kenosha, but also all of the climate catastrophes and natural disasters. Am I being uplifting enough? Ha!

Hello, my beloveds. Long time no see! My apologies for the absence. I’m sure many of you, like me, have been struggling with the continued pandemic, the back-to-school season, and the rather horrifying events taking place around the United States and the world, not least of which are the incidents in Portland and Kenosha, but also all of the climate catastrophes and natural disasters. Am I being uplifting enough? Ha!

As for me, personally? Suffice it to say, I’m busy, busy with the new semester. For some reason, I’ve overloaded myself by two classes (teaching 7 instead of the required 5) and, of course, they’re all online, which adds a particular level of difficulty. If the first ten days of term are any indication, though, I think it’s going to be an excellent, if overwhelming, semester. I’m just now starting to get over an ear infection and feeling well enough to add a blog update to my schedule, so here we go!

August was a pretty great reading month. I’ve continued to focus a lot of my attention on poetry. I’m also thrilled to report that I have a little poem appearing in October. You’ll be able to find it in the Autumn issue of Variant Literature Journal (Issue 5), available in October. I’ll be sure to link-up on my publications page when it becomes available. Receiving that acceptance was so reinvigorating because I’ve been focusing quite a bit on my poetry writing, lately, in addition to novel revisions. I had planned to submit a chapbook manuscript by end of August, actually, but with everything going on personally and professionally, I simply couldn’t manage to get it finished in time. Better to do it well than to do it rushed, right?

Also, without knowing it, I appear to have participated in “The Sealey Challenge,” which is a month-long poetry reading challenge hosted by poet Amanda Sealey. I didn’t discover there was such a thing until sometime around August 26th? So, I don’t count my accidental participation in any real way, but I thought I’d mention it here and spread the hashtag just in case any participants are still keeping up with readers’ adventures. Here’s what I’ve read in poetry this month:

Imago by Joseph O. Legaspi, which is brilliant and important. I’ve linked up my August 7th review of that one. 5 out of 5!

Imago by Joseph O. Legaspi, which is brilliant and important. I’ve linked up my August 7th review of that one. 5 out of 5!

Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys by D.A. Powell. This is my first experience reading D.A. Powell, but I’m thrilled to say we’ve recently connected on Twitter. He’s an extraordinary talent and this one felt like such a personal event for me. 4 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Feed by Tommy Pico. I’ve been meaning to read Pico for a long time. I have two of his collections, and I’m sure I’ll get to the next one very soon. That said, I think this one is part of a series, perhaps the final installment? Which means I’m reading out of order. I have no idea if that matters. Pico’s voice is witty and restless. He’s creative in ways that are difficult to understand, nevertheless describe. A more comprehensible automatic writer than, say, William Burroughs, though not quite so audacious. 3 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Bury It by Sam Sax. So, Mr. Sax is another accomplished poet who is a recent discovery for me. I’ve got two of his collections as well, and I was admittedly blown away by this one. I marked so many poems in this one that I thought about just trying to re-read it again and again until I had them memorized. It’s safe to say that this one, along with Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds and Legaspi’s Imago, will be a repeat guest. 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Burnings by Ocean Vuong. Listen, I can’t even get started with Ocean Vuong. He’s too much. I don’t want to say he’s a perfect writer, but to me, he is. I’m drawn into his words so deeply every time. I was extremely lucky to be able to find a copy of this one, as it was a limited print and it’s terribly hard to find (and very expensive!) It’s worth both the hunt and the cost, though, to have one of these to call my own. I’m torn between wanting to be Ocean Vuong and wishing he’d get out of my head! 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Burnings by Ocean Vuong. Listen, I can’t even get started with Ocean Vuong. He’s too much. I don’t want to say he’s a perfect writer, but to me, he is. I’m drawn into his words so deeply every time. I was extremely lucky to be able to find a copy of this one, as it was a limited print and it’s terribly hard to find (and very expensive!) It’s worth both the hunt and the cost, though, to have one of these to call my own. I’m torn between wanting to be Ocean Vuong and wishing he’d get out of my head! 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Guillotine by Eduardo C. Corral. This one was strongly recommended by Vuong himself, and for good reason. Corral’s poems explore the gritty truths about migration and life at the southern U.S. border. He dances with issues of sex and romance, culture and individualism, and a quiet spirituality, the kind that belongs to an individual, not to a culture or organization. I enjoyed this one. 4 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Chelsea Boy by Craig Moreau. I think what I enjoyed most about Moreau’s poems are their playfulness with language and metaphor. Poetry is supposed to do that, of course, but I found myself often being surprised by the way Moreau saw or described something, usually something commonplace. I picked this one up because, like those listed above, it is a collection of gay male poetry, and that’s where my head and heart are at right now. It’s described as giving voice to “sex, sadness, beauty, and truths,” so how could I miss it? 3 out of 5 on Goodreads.

An American Sunrise by Joy Harjo. If you’re curious about why Harjo is the United States poet laureate, here’s a good place to find out. Wow. Somehow, whether it was coincidentally or subconsciously intentional, I ended up reading this one alongside of An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Let me tell you, that was a powerful and maddening experience. I found myself designing a history-literature course while I worked my way through the two. Harjo’s poems are sometimes beautiful, sometimes almost prayerful, but often biting and brutal condemnations of what we have done to native North American people, and what we continue to do. “That’s how blues emerged, by the way– / Our spirits needed a way to dance through the heavy mess. / The music, a sack that carries the bones of those left alongside / The trail of tears when we were forced / To leave everything we knew by the way–” An incredible collection, and one that offers perhaps the perfect survey for political candidates’ fitness for office. 5 out of 5 on Goodreads.

Other books I read in August:

Other books I read in August:

- The Art of Communicating by Thich Nhat Hanh. 4 out of 5 on Goodreads. I really enjoy reading Hanh’s explorations on life and living. In a loving voice, he reminds us about what is important and helps us pause amidst the difficulty to reassess, slow down, and breathe.

- America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan 4 out of 5 on Goodreads. One of the most important migrant stories, this one is the autobiography of Filipino-American writer who left the Philippines for the United States and a better life. What he found was racist abuse, economic impoverishment, and disease. Bulosan’s is not a happy story, but despite all his hardships in the United States, he continued to believe in its possibility, right up until the day he died.

- An Indigenous People’s History of the United States 5 out of 5 on Goodreads. A truly powerful and fury-inducing “revised” history of the United States. I’m sad to say that I learned a lot about our history from this book, including some important information about a few of my personal heroes. I’m now left rethinking a lot about who we are, now, and how we can be better.

By the way, I’ve also started participating in a pen pal exchange. I’ve got two pen pals at the moment, but I’d be happy to take on more. If you’re interested, let me know. If there’s a lot of interest, I could even start an exchange system and share it here for anyone who wants to join. Snail mail is nice, when it’s not bills or junk! And it’s a great way to support the U.S. Postal Service.

By the way, I’ve also started participating in a pen pal exchange. I’ve got two pen pals at the moment, but I’d be happy to take on more. If you’re interested, let me know. If there’s a lot of interest, I could even start an exchange system and share it here for anyone who wants to join. Snail mail is nice, when it’s not bills or junk! And it’s a great way to support the U.S. Postal Service.

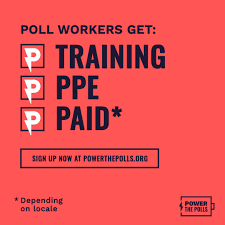

How are you doing? Reading, writing, or watching anything interesting, lately? Staying healthy and safe? And, if you’re a U.S. Citizen, are you registered to vote? I’ve signed-up to be a poll worker this year, which I haven’t done in a very long time. It’s important, though, given the state of affairs in this country and due to the pandemic and its implications for elderly individuals in particular (those who make up the majority of poll workers). Please consider volunteering. I found out how to do so in my state by visiting http://www.powerthepolls.org.

8 More Rapid Reviews

Posted on August 7, 2020 by Adam Burgess

As promised in 8 Rapid Reviews, Part 1, here are the other eight books I’ve read recently but haven’t had the chance to properly review. I’m not going into much depth on these because, well, I just want to get caught up! But I did appreciate all of them and thoroughly enjoyed some. Just like last time, I’ll include my Goodreads rating in order to provide a snapshot of just how much I liked each one of these, in general terms.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, by Robin DiAngelo: I have to admit that this one took me a bit longer than usual to get through, particularly as it’s not very long. There was something about it that unsettled me a bit and I still haven’t been able to identify it clearly. I will say, I’ve read a couple of scathing reviews for it, where people have called it condescending and counterproductive. I sat with my thoughts about those reactions for some time and haven’t been able to agree. I think some of the problem is, first, the people who have responded to the book that way seem to have a particular agenda/ideology of their own and, second, some of them clearly have not read the book or are not the intended audience for it. This is is a book written by a white woman whose intended audience is other white people, especially those who call themselves allies, want to be allies, or believe themselves to be, but who continue to perpetuate racism in smaller or larger ways. DiAngelo’s definitions were helpful, but not quite as helpful, in my opinion, as Ibram X. Kendi’s. Similarly, her shared experiences were helpful but not quite as–what’s the word, genuine?–helpful as Kendi’s. Is it a valuable supplement, though? Absolutely. I learned a lot from what DiAngelo shares and from her particular expertise in diversity training. Despite some hiccoughs in the messaging, I believe what she is sharing is true and that those approaching it with a genuinely open mind and open heart, will gain from the experience. 4 out of 5.

Don’t Call Us Dead, by Danez Smith: I’ve been reading an awful lot of poetry this summer, probably because I’ve been focused on writing my own while I revise my third draft of my novel and prepare it for submission/query. This one, though, is a standout among the dozen or so that I’ve read since May. Smith tackles head-on (and in the very first poem) issues of police violence and black death. But he also illustrates, beautifully, experiences of grief and love. Some of his poems are musings on morality, others are stark and naked explorations of desire and sexuality, including the HIV experience. It is, really, a complex and complicated journey describing one poet’s existence as an American, and he reminds us of James Baldwin’s righteous truth that anyone who claims to love this country is duty bound to recognize its flaws and to demand better from it. “take your God back. though his songs are beautiful, his miracles are inconsistent.” Really stunning. 5 out of 5.

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, by Chen Chen: This collection was chosen by Jericho Brown, one of my favorite contemporary poets, for publication and award, which immediately piqued my interest. Chen Chen’s poems run the gamut of emotions, from tender to ferocious, as its description indicates, and he describes in ways both blunt and subtle experiences with sex and romance. Writing from the perspective of an Asian-American immigrant, some of the most striking poems are the ones in which he describes his memories of coming out and his parents’, especially his mother’s, strong negative reactions to it. The reader/listener is invited to witness the poet’s life, like an autobiography in verse, and to share his joys and sorrows, griefs and hopes. “I was 13 & it was night & all night I stared / at the moon from my tree, willing myself to think / not of them, but of how it would taste / to kiss, to be kissed, oh / moon, for a long time, for the first time / . . . / oh / moon, hungry moon, unkissed / & silent, I would kiss you.” 4 out of 5.

Where We Go From Here, by Lucas Rocha: I honestly can’t remember how this one even got on my radar, but I remember reading a review for it, somewhere, and noting that this one was a recent translation from Brazil. The combination of being an LGBTQ novel, in the young adult genre, that covers life with HIV, and that was written and published originally in South America, was too much for me to turn away from. I don’t read nearly enough South American literature and this seemed like a decent way to correct that, somewhat, particularly at a time when I was reading a lot of heavy material and could use a little YA break. The story is told from three perspectives, two young men with HIV and one without (but who thought he might have it). I appreciated the fact that the author provides multiple perspectives on living with HIV, including the good and the bad, the optimistic and the pessimistic, and also that it is a contemporary example featuring young adults (much HIV/AIDS literature is decades old at this point, and often features older characters; it is also, unfortunately, often fatalistic.) A relief to read a mostly joyous story of people who just happen to be living with HIV. I did have some trouble with the narrators (they were not distinctive enough from each other, for me) and with the repetitive storytelling, but overall, a valuable read. 3 out of 5.

Imago, by Joseph O. Legaspi: As I prepare to teach my Southeast Asian Literature class this fall, I wanted to dive into some SE Asian literature that is not on my required reading list but that might offer me more perspective and experience, including possible recommendations for students who are interested in reading more. This was an incredibly fortuitous place to start. Legaspi’s poems cover his time in the Philippines as a young boy and, later, his life in the United States. His poems are often classically erotic, even as the pertain to family–his father, mother, and brother. This was striking at times, and unusual, but wholly beautiful and necessary in telling the story of his life as he experienced. In one poem, he writes about transforming from boyhood to manhood, “I then thought of others at the verge of their manhood: / my brother to replace me on this stool, / a neighborhood of eleven-, twelve-, and thirteen-year-old / boys wearing the skirts of their sisters / and grandmothers, touched / by the hands of their mothers, / baptized by green waters, / and how by week’s end / we will shed our billowy skirts, / like monarchs, and enter / the garden of our lives.” What an absolutely breathtaking way to describe what must be one of the most physically painful experiences–and memories–imaginable. This, I found, is something Legaspi managed to do throughout his entire collection. He looks at life, at himself, and at his loved ones, in ways that seem improbable, if not wholly impossible, and makes us understand, no, makes us feel what only he could have felt. One of the few perfect poetry collections I’ve ever read. 5 out of 5.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, by Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley: I had been on the hunt for this book for nearly a month, when a dear friend sent me her copy. Thank you, Crystal! I had read this one way back in junior high but could barely remember anything about it. I did remember a few flashes from the film adaptation with Denzel Washington. I can even remember where I was when I watched the movie, which is to say, it definitely left an impression on me. I think what I admire most about Malcolm X, aside from his courageous altruism and his great personal and professional successes despite limited education and a tumultuous childhood, is that he had a genuine ability to think critically about a situation of which he already had a deeply held belief or opinion, and then change his mind. That’s a rare thing, perhaps now especially. It was not a comfortable read, given Malcolm X’s opinion of white people for most of his life and as told throughout most of the book, but watching his progression, watching his mind and heart change, is one of the more unique experiences available to any reader. This is an autobiography that is not just a personal history or a social history or an ideological critique; it is the living, breathing philosophy of a man on display, with all its faults and with its extraordinary developments, presented much like a gift to the reader, to view in real time. Haley’s afterword is also remarkable. 4 out of 5.

Swimming in the Dark, by Tomasz Jedrowski: “Your face. It looks like something’s opened up, something that was folded tight. Like a fist. I’d never noticed it before, but now I do.” This book took my breath away. When I finished it, I wrote down a single line: “Thank you, Tomasz.” Swimming in the Dark is a rich and daring tale set in 1980s Poland. Its backdrop is the decline of communism in the nation and the rise of something new. Wading through that transition are two young men on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. One, the narrator Ludwik, cannot abide the communist state and its restrictions, prejudices, and invasiveness. He loses his first close friend, Beniek, to bigotry against Jewish people in Poland at this time, a loss that will change and haunt him forever. The other, Janusz, having come from extreme poverty and worked his way up, through education, into a stable and rewarding position in the communist party, cannot imagine defying it. The two fall in love and, just as the country is torn apart politically, Ludwik and Janusz are bombarded by the many obstacles of being gay in the 1980s, in a country where it is not explicitly outlawed but where any deviation from the norm is an affront to the party. Jedrowski’s prose is lyric and emotive, matching brilliantly the narrative’s tone and atmosphere at every point. 5 out of 5.

The Nickel Boys, by Colson Whitehead: “We must believe in our souls that we are somebody, that we are significant, that we are worthful, and we must walk the streets of life every day with this sense of dignity and this sense of somebody-ness.” Based on a true story, which is referenced extensively in the afterword, The Nickel Boys takes place just as the Civil Rights movement begins in the United States. Its protagonist, Elwood Curtis, is an unusual boy in the neighborhood. Polite, introverted, and perhaps a bit of a nerd, he is inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s non-violent movement and dreams of attending college, soon. Indeed, his dream is about to come true–one of the first in his neighborhood for which this will be true–when life takes a terrible turn and everything changes. What follows is the story of a boy, wrongfully convicted and sent to a juvenile prison, progressively labeled a “school.” Here, he meets young Turner, Elwood’s opposite in nearly every way. The two use their own unique resources and abilities to survive the Nickel Academy and all its horrors. For as long as they can. I would love to say that Whitehead has invented something profound, here; a historical metaphor for modern American life, but unfortunately, a version of this school (let’s face it, many versions) really did exist, and a version of Elwood’s life (let’s face it, many versions), really did exist. Whitehead’s research is sound and detailed, though, and he fills in the narrative gaps with creative honesty and delicate rage. It’s no surprise this one won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 4 out of 5.

Thanks for reading through my mini-reviews for these most recent eight reads. It’s funny, lately there’s been this huge discussion online over whether or not we should review (negatively) books that we did not enjoy. I come down mostly firmly on the side that there’s no point or purpose in sharing negative thoughts about books I didn’t enjoy because the purpose (to me) of writing and sharing reviews is to recommend books to others who might also appreciate them. So, if I didn’t like it, why waste my time? That said, I’ve also discovered that, as I’m nearing 40-years of age and three full decades of ravenous reading, I tend to pick books that I’m pretty sure I’ll like in the first place. I guess we readers know ourselves pretty well, right? Anyway, that’s all a long-winded way of saying, I’ve read a lot of great stuff this summer and I hope you’ll get to enjoy some of these, too!

The Classics Club Spin #24

Posted on August 3, 2020 by Adam Burgess

Update: The Spin has pulled #18. Blah.

Here’s a little confession: There have been 23 Classics Club Spins (soon to be 24), and I’m pretty sure that I’ve only ever finished one or two of them. What a terrible track record! Maybe I can adjust the percentage a little bit with this new one, eh?

What is the Spin?

It’s easy. At your blog, before next Sunday 9th August 2020, create a post that lists twenty books of your choice that remain “to be read” on your Classics Club list.This is your Spin List. You have to read one of these twenty books by the end of the spin period.

On Sunday 9th August, the Classics Club will post a number from 1 through 20. The challenge is to read whatever book falls under that number on your Spin List by 30th September, 2020. I’ll come back and highlight the one that corresponds with that number on my list.

My Spin List.

- North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell

- The Seraphim and Other Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Doveglion: Collected Poems by José García Villa

- Our Village by Mary Russell Mitford

- The Hanging on Union Square by H.T. Tsiang

- The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood

- Middlemarch by George Eliot

- At Swim, Two Boys by Jamie O’Neill

- Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder

- Paradise Lost by John Milton

- Kim by Rudyard Kipling

- The 120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade

- The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish

- The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe

- Dead Souls by Nikolay Gogol

- Metamorphoses by Ovid

- Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

- Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

- One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Wish me luck!

8 Rapid Reviews

Posted on August 2, 2020 by Adam Burgess

I’ve been reading voraciously this summer but have definitely not been keeping up with reviews! I think that’s in large part due to the fact that I was teaching three classes and involved with two (now three – ha!) important and in-depth professional projects this summer. It’s unfortunate that I didn’t get any significant thoughts down on much of this summer’s reading, because I’ve been reading so many really incredible things. That said, I do want to at least share what I’ve read, with a brief note or two about each work. I’ll include my Goodreads rating, too, for whatever that’s worth.

Fire to Fire by Mark Doty: This 2008 collection (I thought it was more recent but am now realizing I’ve literally had this sitting on my shelves for twelve years!) is actually a kind of “greatest hits” plus ample selection of, at the time, new works. It gathers together the “best of” Doty’s previous seven poetry collections and adds his more recent uncollected pieces. What it proves is that Doty is one of America’s greatest contemporary poets and certainly a standout for gay poetry. I responded most to his poems about loss and about the painful but necessary act of moving forward. 5 out of 5.

Fire to Fire by Mark Doty: This 2008 collection (I thought it was more recent but am now realizing I’ve literally had this sitting on my shelves for twelve years!) is actually a kind of “greatest hits” plus ample selection of, at the time, new works. It gathers together the “best of” Doty’s previous seven poetry collections and adds his more recent uncollected pieces. What it proves is that Doty is one of America’s greatest contemporary poets and certainly a standout for gay poetry. I responded most to his poems about loss and about the painful but necessary act of moving forward. 5 out of 5.

You Get So Alone At Times that It Just Makes Sense by Charles Bukowski: Another poetry collection from another American master. It was interesting to read this immediately after the Doty collection. I was both surprised by its sensitivity and simultaneously reminded of Bukowski’s grit and candor, for which he was much admired. I had not read much Bukowski, besides a few random poems found online and his novel, Ham on Rye. Bukowski was more a poet than anything, though, so it was great to finally sit down with one of his intentional collections and to experience a span of his work in action. I enjoyed it much more than I thought I would, probably because I found it more intimate and sensitive than I imagined it would be. 4 out of 5.

The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas: Why didn’t I like this one? Honestly, this was such a weird experience. It read to me like a lampoon, but I’m not sure that was the intention. Maybe it’s because I recently read The Princess Bride and found it so hilarious, such an effective parody, that returning to the original genre of a type of Chivalric Romance just seemed, well, a bit absurd and unnecessary. I might also have found it a bit too glib for the serious kind of reading I had been doing this summer, otherwise, mostly relating to the Black Lives Matter movement and diversifying my reading, as well as a focus on poetry which, even when it’s fun, is serious work. Anyhow, it wasn’t all bad, of course; it’s a classic for a reason. I particularly appreciated how much depth some of the women characters received and there were some plot twists that I did not see coming. I don’t think I’d read this one again, though. Should I give Dumas another try? Count of Monte Cristo, maybe? On the plus side, this is another book completed for my Back to the Classics Challenge. 3 out of 5.

No-Nonsense Buddhism for Beginners by Noah Rasheta: Noah Rasheta is the host of Secular Buddhism, an interesting podcast that explores a different element of Buddhism or Buddhist living (or everyday living through a Buddhist lens). In this book, he lays out the fundamental principles of Buddhism and attaches each to contemporary, real life scenarios to help new practitioners understand the many ways that a Buddhist life manifests. I appreciated how clear and organized, and brief, this book is, as it meets its promise of being “for beginners.” It’s an excellent starting point that provides a road-map for how to proceed with more in-depth study of the various concepts and principles, and it offers a helpful bibliography at the end, too. I also very much appreciate Buddhist instruction from people who are living a contemporary American life, as that is a lifestyle that seems, generally speaking, antithetical. 4 out of 5.

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison: This is another I read for BLM and it was also on my list for Back to the Classics & the Classics Club. What a beautiful, sad, powerful first novel from another American master. I’ve been thinking about the three Morrison novels I’ve read–Beloved, Sula, and now The Bluest Eye–and trying to articulate what it is about Morrison that makes her work so impressive and so dangerous. In researching this one a little bit, I learned that Morrison was disappointed in herself for writing it the way she did. She admitted, later, that she had hedged a bit for white audiences, refusing to say exactly as much as she had intended, and in the way she intended to say it. I found this surprising because it’s such an interesting book, and damn good, and its intention seems clear enough to me. But then I do look ahead to Sula, and ahead again to Beloved, and I begin to see what she means. Over the course of her life and career, Morrison really cast off any regard for unintended audiences and focused specifically on the stories she needed to tell and the audiences she wanted to reach. Her masterpieces are then crafted out of the combination of supreme talent but also a sharp awareness of her particular rhetorical situation. The Bluest Eye hints at these, but doesn’t perhaps achieve the way Beloved does. Nevertheless, I’ve read that, for some readers, Bluest Eye changed them. Changed the way they saw the world. And I can absolutely appreciate why this would be so. 4 out of 5.

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison: This is another I read for BLM and it was also on my list for Back to the Classics & the Classics Club. What a beautiful, sad, powerful first novel from another American master. I’ve been thinking about the three Morrison novels I’ve read–Beloved, Sula, and now The Bluest Eye–and trying to articulate what it is about Morrison that makes her work so impressive and so dangerous. In researching this one a little bit, I learned that Morrison was disappointed in herself for writing it the way she did. She admitted, later, that she had hedged a bit for white audiences, refusing to say exactly as much as she had intended, and in the way she intended to say it. I found this surprising because it’s such an interesting book, and damn good, and its intention seems clear enough to me. But then I do look ahead to Sula, and ahead again to Beloved, and I begin to see what she means. Over the course of her life and career, Morrison really cast off any regard for unintended audiences and focused specifically on the stories she needed to tell and the audiences she wanted to reach. Her masterpieces are then crafted out of the combination of supreme talent but also a sharp awareness of her particular rhetorical situation. The Bluest Eye hints at these, but doesn’t perhaps achieve the way Beloved does. Nevertheless, I’ve read that, for some readers, Bluest Eye changed them. Changed the way they saw the world. And I can absolutely appreciate why this would be so. 4 out of 5.

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta: Wow, this was not what I expected! In the first place, it is a novel in verse. I also thought, for some reason, it was about the transgender experience, perhaps because I had read Felix Ever After not long before. The book’s description, though, says it best when it states, “Sometimes, we need to take charge, to stand up wearing pink feathers – to show ourselves to the world in bold colour.” That’s exactly what the story is about. The protagonist’s story unfolds in poetry. He deals with an absent father and with “non-boyish” desires. He likes pretty things and pretty colors, and he’s not sure why, as a young boy, he’s told that he can’t want the pink flamingo because it’s for girls. He’s not sure why he has to hide the barbie doll that he so cherishes, or pass it on to his sister. This one was really lovely and an excellent, positive addition to my BLM reading for the summer. It supplemented, and provided a needed break from, the non-fiction anti-racism reading. 4 out of 5.

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang.Somewhere amidst all the very heavy reading I was doing this summer, I apparently needed a break. That break was found in Jen Wang’s delightful graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker. The story is about a young man, a prince, who sometimes likes to dress in women’s clothes. He hears of a brilliant young dressmaker and hires her to be his own personal designer. The story is charming, delightful really, and fresh in the way it bends gender roles separate from sexuality. The art, too, is simply wonderful. The story has its ups and downs, of course, and nothing goes entirely smoothly, not even for a prince, but the ending is a dessert worth waiting for. What a gem this one is! 4 out of 5.

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang.Somewhere amidst all the very heavy reading I was doing this summer, I apparently needed a break. That break was found in Jen Wang’s delightful graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker. The story is about a young man, a prince, who sometimes likes to dress in women’s clothes. He hears of a brilliant young dressmaker and hires her to be his own personal designer. The story is charming, delightful really, and fresh in the way it bends gender roles separate from sexuality. The art, too, is simply wonderful. The story has its ups and downs, of course, and nothing goes entirely smoothly, not even for a prince, but the ending is a dessert worth waiting for. What a gem this one is! 4 out of 5.

The Malevolent Volume by Justin Phillip Reed. Another excellent poetry collection by a gay black poet. This one speaks directly to the current movement and to the violence that has been perpetrated against black bodies for so long, too long. Reed uses a full arsenal in his exploration and call to arms, from mythology to modern cinema, from pop culture to classical poetic forms. At its heart, this is a critique of exploitation, an expose, and while it often looks outward at the populations of marginalized people, it is also personal, intimate, and revolutionary. Reed’s style of free verse is deeply informed by structure, which is exactly something I’ve been trying to explain to my students for years. His poems are always in conversation with other poems, other poets. This will become a model of how it is done. 4 out of 5.

Thank you for reading Rapid Reviews, Part 1, which contains my brief thoughts on eight summer reads; Part 2 will come soon and will include brief thoughts on another eight reads from this summer. (And I’m also reading three more books right now, so those will come, well, someday!)

900 Miles by E.J. Runyon

Posted on July 21, 2020 by Adam Burgess

I was first introduced to E.J. Runyon as a writer via her 2012 short story collection, Claiming One. I was a big fan, then, and I remain a big fan today, having just completed my first read of her new novel, 900 Miles.

I was first introduced to E.J. Runyon as a writer via her 2012 short story collection, Claiming One. I was a big fan, then, and I remain a big fan today, having just completed my first read of her new novel, 900 Miles.

One of the things that first impressed me about Runyon’s writing style is her ability to capture voice. It is impossible for me to enjoy a story that cannot manage to get its characters’ perspectives right. I found Runyon’s adroitness at this especially apparent in Claiming One because each story’s distinct narrator had a clear and unique voice. I think this is one of the most challenging things for writers to do and is much of the reason why short story writers, in particular, often succeed or fail as storytellers. When we read ten or twelve or however many stories in a single collection, often binging a few in a sitting, it becomes very clear which writers can create disparate narrative voices and which ones simply rely too heavily on their own. Runyon has the knack.

I was immediately drawn into the story 900 Miles tells because of the perspective of its narrator, Christina. It is remarkable to see such growth in an individual character, one whose presence remains the majority of the story itself from start to finish, develop in such a short period of time. I’ve read some trilogies that don’t quite manage this, and yet what Runyon does for Christina is not only believable, it is a privilege to witness. In the span of a couple-hundred pages, Christina’s life changes. The event that causes it is momentous, but the way she reacts to it, with caution and care, allows her to experience the kinds of living opportunities she had to that point forfeited due to poverty and self-consciousness. I’ll admit that I was worried about the striking nature of Christina’s change in fortune, and about how early it comes in the narrative, but that’s just a lesson: trust the author, especially one as precise as Runyon!

Another element I found interesting about this short but thoughtful novel is its design. The chapters are separated into mini-portions, somewhat like vignettes. This took me back to my first experience reading Justin Torres’s We the Animals. Part of why I loved that short book so much is because it unfolded in moments, in flares of color and passion. Christina’s story, too, in 900 Miles, is both slow and fast. Everything changes in an instant, and yet Christina doesn’t allow that instant to change or define her. Instead, she embarks upon an arduous journey of self-discovery. As she gets in touch with her feelings, her desires, her limitations, she relays those to the readers in bursts of awareness. These vignettes propel the story forward but they also help us experience Christina’s moments of movement, to literally notice the changes as they happen, one at a time and then, holistically.

There is as much about 900 Miles that is sad as there is about it that is happy. And yet, that’s life, isn’t it? Our journey, be it 9 miles or 900, often unfolds behind us. We recognize it only in memory, in retrospect. The beauty of a book like this is that it reminds the reader how special it can be to slow down just a little bit and breathe our moments as they come.

Note: I received an electronic copy of this title from the publisher, Inspired-Quill; however, I still can’t manage to get through a damn ebook. So, I bought a print copy myself. No regrets.

Disclaimer

All original written material and images located within RoofBeamReader.com, including its pages, posts, and comment boxes, are copyright of the website author. Permission to use, reprint, or publish any material, including articles, blog posts, or book reviews from the Roof Beam Reader website, whether in print or online, must be granted by the author in writing.