Roof Beam Reader

Adam Burgess

Mostly History

I’ve decided that I’d like to devote my reading time this summer to biography and history. In the last few years, I’ve read a lot of history, particularly “people’s history” or “revisionist” history—you know, those things that are typically left out of traditional education curricula in the United States.

I haven’t devoted specific time to it, though, except in mini-projects, such as Black History Month, etc. And I’ve read so few biographies in general that I began to think I had to change that, especially since there are so many people who interest me. I’ll be reading some literature this summer, too (novels, poetry), but for the most part, I’ve got biography and history on the agenda, and that’s certainly how the month of June turned out. Here’s where I’ve been:

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson (5 out of 5)

This is the first biography by Isaacson that I’ve read. It has certainly encouraged me to read pretty much any others that he’s written. Fortunately, he’s written a bunch on people I’m actually interested in learning more about! He’s got a kind of collection known as “the genius collection” or something like that, which includes Leonardo Da Vinci (read this month, too), Benjamin Franklin, and Steve Jobs. He’s also got another one called The Innovators that looks fascinating, and The Code Breaker, about Jennifer Doudna, also looks great. I found Isaacson a bit repetitive in this one, but it wasn’t so much as to be distracting or annoying. What struck me most about Einstein, through this biography, is how very similar he and I are in personality and politics (leaving aside the genius part, obviously). I knew a little about Einstein’s major achievements, of course, but there is so much more to know, and Isaacson tells the story of his life very well. I enjoyed it so much that I immediately went out and purchased Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson (4 out of 5)

We toss around this word, genius, until its definition is meaningless. I thought I knew Leonardo da Vinci. Don’t we all? We hear about him as children (in my case via The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, first, but never mind) and then throughout our lives. Most of us recognize that he was a true genius, in the sense that is actually meaningful. We’re awed by his art and inspired by his inventions. But it turns out, we knew nothing. I knew nothing. I had not a g-damn clue. I’m not sure I’ve ever finished a book, biography or otherwise, feeling so humbled. And a little bit enraged. What if Leonardo had published his papers? Who and where would we be now? A hundred years more advanced than we are? Two hundred? Goodness gracious! Isaacson’s tendency to be repetitive did get a bit distracting in this one, possibly because he does not arrange this biography in a straight chronology the way he did Einstein’s. Still, it was an edifying and exciting adventure and very much has me wanting to return to The Agony and the Ecstasy, Irving Stone’s biographical novel about Michelangelo.

A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski (4 out of 5)

I first read this one back in 2015 or so, while preparing/writing my doctoral dissertation. I’m certain I referenced it once or twice, too. If I’m not mistaken, this is the first text in the “revisionist history” series, and it’s a decent inaugural text for that project. I was and still am disappointed that Bronski ends the history at about 1990, despite the book having been published two decades after that. He explains his reasons for this, but it didn’t change my reaction. So much happened for Queer/LGBTQ+ people between 1990 and 2012, and I think it needed to be represented, too. Otherwise, though, the book is exactly what it says it will be, an illuminating and detailed history of queer people in the United States, from its founding to the AIDS crisis. Those new to LGBTQ+ history will learn a lot from reading this text, some of which will be surprising. We have always been here.

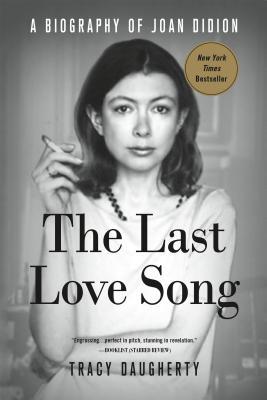

The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion by Tracy Daugherty (3 out of 5)

What a gift to witness Joan Didion grow, and grow up. She was always a great writer. She became a great person. I admire no one more than the person who can face the truth and then change because they’ve faced it. I wasn’t a big fan of the style, here, though I do understand the author had to write this without Didion’s cooperation. If you’ve read all of Didion’s work and seen her interviews, there’s not a whole lot to be gained. That said, the detail (which is fairly criticized as being overwhelming) and chronology, and the inclusion of stories happening/lives being lived in close proximity to Didion’s, while at first irritating (as overkill/unnecessary), eventually made a lot of sense. If you’re writing about a writer who is always looking for the threads, why not include the threads? I think we get closer to a truth that way. I’m not sure I can forgive the biographer for disillusioning me about Didion’s personality–oh, we’d have never been very good friends–but it’s safe to say she remains my favorite writer.

DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi (5 out of 5)

I have honestly never read anything like this. I’m not equipped to remark on it. I think I can say, though, that it is perfect for what it is. It’s inventive, powerful, and jarring. There’s visual poetry and traditional poetry, all of which tells and investigates a painful and disturbing period in American history. It challenges us to see and feel what happened, and to recognize that “we” were responsible for it. This is an incredible piece of work.

The Wrap-Up

So, that’s one history, three biographies, and one poetry collection (which is heavily steeped in history and biography). I’m also currently reading Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg and Things We Lost to the Water by Eric Nguyen. I might end up finishing one or both of these before June is out, but probably not in time to write anything about them, so if I decide to share some thoughts, they’ll likely come sometime in July.

Some Questions

- Should I bring back Austen in August?

- Should I redesign the blog, or does this theme work?

- Should I bring back the Official TBR Pile Challenge for 2022?

- Should I bring back any other events, or would you like to see something different (specific ideas?)

- How are you!? What are you reading?

Switch by A.S. King

Switch is innovative, perplexing, and heartbreaking. In other words, it’s exactly what we have come to expect from the one-of-a-kind mind and talent that is A.S. King. Even among her unique oeuvre, though, this novel stands out as experimental, which might explain some of the rather tepid reviews it has received thus far. It’s hard to prepare readers for a truly surrealist experience, and perhaps that’s especially true for young readers who might be experiencing surrealist literature for the first time. So, how does one prepare to read a book like this?

Well, the best way I can describe Switch is to say that it’s a visual depiction of what happens at the crossroads of trauma, grief, and recovery. Imagine every scenario, every emotion, that manifests from trauma: Isolation, doubt, self-loathing, fear, suspicion. Next, imagine the cause of all this is your own family, the very people (or person) you’re trapped with. And these people are also the ones you must rely on. Got it so far? Now: make that story visible. Literally, tell this story, in words, in such a way as to make the readers see and experience the unraveling of that trauma, that grief, right there on the page in front of them, not necessarily in the prose, but in the construction and deconstruction of that prose. Memories are metaphors. People are tools personified. Can you imagine? I doubt it. And there’s the genius of A.S. King. There’s the brilliance of Switch.

The story itself is told from the perspective of teenager Truda Becker, whose parents are going through a kind of separation, whose older brother is being blackmailed by their sibling over something that sort of did but sort of didn’t happen, and whose sister is a manipulative narcissist hellbent on turning the family members against one another. Truda’s father, in a noble but misguided attempt to heal his family, creates something that changes the world. As a result, many young people are discovering they have certain special abilities, and one of those young people might be Truda herself. What does all this mean? How can the world outside seem totally normal, everyone going about their business as usual, when one’s own home is descending rapidly and maddeningly into a labyrinth of secrets, lies, and makeshift security blankets? And how does one find the courage to right the world again if it means sacrificing her own special abilities in the process?

Why does time stop, how do we get it moving again, and is it worth it to try?

This is an uncomfortable read, and intentionally so. Not only are the themes unsettling, but so too are certain actions and events that are alluded to with greater or lesser detail at different points in the narrative. So, it’s going to be tough to finish reading this story, close the cover, and walk away feeling what we might normally expect to feel after reading a young adult novel: Joy? Elation? Comfort? Well, no, not really, but there’s hope for those things. There’s hope, indeed, in the fact that, despite the visceral, almost painterly displays of trauma the protagonist Truda Becker experiences and depicts, she remains open to love in the end. She remains open to forgiveness—forgiveness, that is, for those who deserve it (including herself); but she also learns how to draw a firm line between herself and those who would harm her, and this is something she, even as the youngest, manages to teach the rest of her family, too.

Grab your crowbar. Flip the switch.

Notable Quotes:

“To understand anything is to understand energy” (24).

“Carrie has been on antidepressants for six months. She has gained eighteen pounds. The people who point out this weight gain to her far outnumber the people who ask how she’s feeling today, or if she feels like dying anymore” (59).

“I think the universe is rewarding me for dismantling Fear” (134).

“This is the solution to fourteen generations of bullshit that we don’t have to pass down to our kids. That’s our job. Generation fifteen. We’ll be the generation who heals” (164).

“Time stopped because it was sick of us being assholes to each other. So the only way to start it again is to stop being assholes to each other” (221).

Snow Day Updates

The weather here in America’s hottest region has been strange this weekend, to say the least. It’s tens of degrees cooler than normal and we’re even getting snow in the mountains! Snow in late-May! It’s quite an event, let me tell you, and I’ve been trying to enjoy every second of it. Soon enough (like, just a few days from now!) we’ll be nearing 100-degree highs. I thought I’d take a little break from enjoying the outdoors, though, to share some reading & writing updates, as well as some “laudable linkage.”

Recent Reading Updates

This month, I’m focusing on Asian American & Pacific Islander writers, in honor of AAPI Heritage month here in the United States. So far, I’ve read four texts:

- In the Country by Mia Alvar. This one is a collection of short stories spanning the Filipino diaspora. The stories are narrated by men and women, in first, second, and third person, and in countries ranging from the Philippines to the United States, to Bahrain. The stories are held together well thematically, and Alvar has a knack for the surprise or dramatic ending, particularly in the shorter stories. What’s most interesting about the entire collection, though, is the many facets of the Filipino experience that it presents for the readers. I imagine Filipino readers will find much to relate with while reading, and others will learn a great deal.

- Threshold by Joseph O. Legaspi was my first poetry collection of the month. Legaspi is also a Filipino-American writer, and his poems reflect the tensions created by his multiculturalism as well as his sexuality. This is the third collection by Legaspi that I’ve read in the last year, and it’s a remarkable one. I might still favor his Imago, but there’s a lot to love and appreciate in this one.

- First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung is a memoir recounting Ung’s childhood during the Cambodian civil war. This is a brutally honest, sometimes graphic portrayal of what happened to Ung, her family, and many others like them when the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, rose up in insurrection against the Cambodian government, destroyed Phnom Penh, murdered anyone associated with the former government or any of its potential sympathizers (including those who worked for the police, those who were considered intellectuals, or anyone else who could pose a threat), and forced many others into work camps or military youth training. Absolutely harrowing and critical story.

- Let It Ride by Timothy Liu is the second poetry collection I’ve read so far this month (I have a re-read of Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds on deck). I’ve only read one other Liu collection to date, Burnt Offerings, which absolutely blew me away, so I was eager to revisit his work. I was not disappointed. While I didn’t quite appreciate this one as much as Burnt Offerings, I still found it a rock-solid collection, tightly themed and generous in its exploration of form. I’ve added several his other collections to my “TBR.”

Currently, I’m reading Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima. It’s funny, about half-way into the book, I felt the urge to learn a little bit about the author. His style intrigued me, as did the story, so I wanted to know who this guy was. While doing some light research, I realized I own two more books by this same author! I’m not sure how I missed that, but I guess it’s a sign that, really, I have too many books! (Is that a thing?)

Recent Writing Updates

Something exciting that’s happened since things have begun to reopen is that I found a new morning writing spot. I don’t want to name names because I’m not particularly interested in giving free advertising, but I will say that it’s a rather large chain which currently has an awesome marketing ploy to get people in the doors. It worked for me! I’ve been a little distracted there, to be honest, because the place gets very busy. That said, it’s so good to be getting back into a routine. For some reason, I’m the kind of person who cannot write well at home. I do all my editing and revising at home, but as far as the original invention and writing/drafting phases? I just can’t do it!

I’ve also just found out that Broad River Review will be publishing one of my poems in their 2021 issue releasing late-Fall. This poem is part of a collection I’ve been working on; it’s very dear to my heart right now, so I’m absolutely overjoyed that Broad River Review liked it, and I can’t wait for it to be out in the world.

Items Worth Sharing

- My dear friend Shannon of Prairie 724 Knots has a wonderful macramé shop filled with all sorts of cool, handmade products. She just made available her PRIDE collection and is donating 25% of all Pride sales to The Trevor Project, which is an organization near and dear to my heart. I hope you will consider supporting Shannon and The Trevor Project!

- Ocean Vuong, my biggest writing inspiration in recent years, has two new poems out at The Yale Review. I think they are both worth reading (and learning from.) “The Last Prom Queen in Antarctica” and “Wood Working at the End of the World.” The last lines of “Wood Working” will take your breath away.

- Andrew Smith, a favorite writer, gave this wonderful interview at James Preller’s blog just a few days ago. It was a great read!

April is the Coolest Month

Hello, everyone, and Happy May Day!

I had an incredibly active reading month in April, so I’m going to post the list of titles that I read (by genre) below, with very, very brief comments on each. I read a total of 16 titles, so there’s just no way I can give any kind of detailed reviews this time around. My focus was on poetry because April was poetry month, but my two favorite reads of the month—and indeed of this year so far—are listed last, under the “Novels” section. P.S. May is Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage month so my focus for the next four weeks will be on AAPI texts (see image at the end of this post.)

And a quick note on writing progress: I’ve submitted two chapbook manuscripts for poetry and have written some new poems, as well as worked on revisions of a half dozen. I’ve got ideas for another half-dozen poems jotted down in note form & hope to work on those this month. I’m also working on a new(ish) novel. Poetry has been my focus, though, and I’ve been reading a lot about it from a craft perspective. It’s also the current strand of coursework that I’m pursuing at UC Berkeley right now (I’m in the creative writing program and will be completing work in fiction and poetry, but right now I’m tuned into the poetry track.)

What I Read in April:

Poetry

- On Poetry by Glyn Maxwell: I think I gave this one a 3 on Goodreads. I thought a lot of the poetry lessons that this teacher incorporates are interesting and engaging, but the overall style and construction of this book on the craft of poetry was not for me. That said, I did place a flag on almost every writing lesson page & plan to keep the book at hand for generative phases/practice.

- Thirst by Mary Oliver: All things considered, Mary Oliver is not a poet I should enjoy. She writes a lot about religion and spirituality from a Christian perspective. So many of her poems are kinds of prayers and praisesongs. Nevertheless, Oliver is a revelation. When she writes about nature, about gratitude, about loss, and yes, even about religion, she writes with an inexplicably simple catharsis. Her lines are simple, her forms recognizable, and yet both form and line, word choice and image, are masterclass.

- Breaking Glass by Jean Valentine: This is my first time reading Valentine, and I’m not sure she’s one I’ll return to often. She’s a National Book Award-winner for poetry, though, and her mastery of craft is apparent. I especially loved two poems from this collection, “Diana,” a short standalone, and Lucy, which is actually a mini-collection of poems about the earliest known hominid. That exploration was utterly fascinating.

- This Way to the Sugar by Hieu Minh Nguyen: Oh, gosh, did I enjoy this collection! I flagged seven poems as particularly interesting to me. I responded mostly to the themes and content of these poems, but Nguyen also has quite a few interesting and effective form poems in here that were edifying. I’m not sure if this collection is as tightly connected as his Not Here poems, but there are definitely close threads and I loved it just the same.

- New Hampshire by Robert Frost: This collection contains some of Frost’s most famous and instructive poems, including “Nothing Gold Can Stay” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” I also fell in love with poems like “The Lockless Door” and “Fire and Ice.” Frost is noted as one of America’s master poets for good reason, but overall, I was not enamored with the collection in total. That said, I did think the title poem (“New Hampshire”), which I had never read, was excellent. What an interesting balance of seriousness and play.

- He’s So Masc by Chris Tse: This poet is a New Zealander of Chinese descent, a unique perspective that added great interest to the poems thematically. I also loved being invited to witness an outsider’s perspective on places like New York City, which is a fun contrast to, say, O’Hara’s Lunch Poems, which I read last month. I flagged six specific poems in this collection as ones to return to, including “Summer Nights with Knife Fights,” “Release” (which contains one of my favorite poetic lines recently read), and “I Was a Self-Loathing Poet.” I came close to giving this one and Nguyen’s collection 5s on Goodreads.

- Wade in the Water by Tracy K. Smith: Not too long ago, I read Smith’s Life on Mars collection. I was not the biggest fan of that one, though I did like several its individual poems. I much preferred Wade in the Water and found it to be good evidence as to why Smith was named Poet Laureate of the United States. Two poems that stood out to me were, “The Angels” and “Unrest in Baton Rouge.”

- The Seven Ages by Louise Glück: Here’s another poet, like Jean Valentine, who I think we’re supposed to love. There’s been a lot of talk about these two in poetry-land recently (Valentine having passed away not too long ago & Glück having just won the 2020 Nobel Prize for literature). I just didn’t feel this collection. Again, in studying craft, this is super helpful, but the poems styles and themes weren’t what I’m drawn to (no fault of the poet!) That said, “Quince Tree” blew me away. I started marking pieces of the poem and ended by basically circling and underlining the entire thing.

- Subways by Joseph O. Legaspi: I was such a huge fan of Legaspi’s collection Imago that I bought his other two collections immediately after finishing that first one. I didn’t respond much to this one, though, and in fact, I can’t clearly recall a single poem from this collection. That said, I’m still very interested in Legaspi’s work and am looking forward to reading the third collection, Threshold, this month for AAPI Heritage. (I think Legaspi has one more chapbook out there somewhere, but I haven’t found it yet.)

- Indecency by Justin Phillip Reed: It’s safe to say that Reed remains one of my favorite contemporary writers. I was crazy for The Malevolent Volume but might have enjoyed this one even more. I gave both collections 4s on Goodreads, but this one came very, very close to my only “5” for poetry this month. The most recent 5 I gave in poetry was to Adrienne Rich, so that’s saying something. (By the way, I read, what, sixteen books this month? I only gave two of them perfect scores. So, a 4 is grand. This is just a disclaimer for all those nutty nuts who have been going bonkers about “less than perfect” ratings on Goodreads. Shush. You’re not cute.)

Fiction Collections

- Dusk Night Dawn by Anne Lamott: I love reading Anne Lamott. It’s an odd writer-reader relationship, considering her personality (in real life) would probably irritate me to no end – I don’t think she’d mind me saying that) and considering she writes a lot about Christian faith, which is something that a) I don’t share and b) I tend to bore of rather quickly. But Lamott is refreshingly real. She doesn’t just own her struggles, failures, and hypocrisies, she invites others in to witness them, laugh at them, learn from them. Despite her penchant for self-doubt, I think this is a sign of an incredibly confident and competent writer. In this collection of essays, Lamott connects her own fears and exasperations that have been exacerbated by the Trump era with personal experiences and universal relatability. To be so honest and effective a writer is something I think I’ll only ever be able to strive for.

- Men Without Women by Ernest Hemingway: I picked this one up after watching the new Hemingway documentary, which I thought was well done and which essentially substantiated a theory I wrote about Hemingway many, many years ago. I think I’m one of those weird outliers who prefer Hemingway’s novels to his short fiction. Well, no, I don’t think it, I know it. What I mean is, I guess the fact that I prefer his novels is what makes me a weird outlier, because everyone else seems to come down clearly on the side of his short stories. I was bored by this collection, to be honest. There are some incredible gems in it (“Hills Like White Elephants”; “A Simple Enquiry”; “Ten Indians”; and “An Alpine Idyll”), but it didn’t leave me in any rush to read more of his short fiction. It did, however, make me want to re-read his novels. His voice, what he can do with a sentence, is no joke.

Novels

- The Secret History by Donna Tartt: I’ve got a few bookish friends who have been on my case (in friendly fashion!) about finally reading this one. I’m glad I did! The whole “dark academia” genre is one I’ve been into since my earliest reading days, when I discovered books like A Separate Peace (and I suppose even Catcher in the Rye might fit into this somewhat.) While reading, I was surprised to learn the “big reveal” right away, and even more surprised to reach what seemed to be the conclusion of the book less than halfway through. It soon became clear to me, though, that this book is about the psychological fallout of an action rather than the action itself. This seems to be one of the, hm, misconceptions about this book from a great deal of reviewers online. I think too many people confused the end of the action with the end of the story, but that was just the beginning. Where a lot of readers were let down by that, I loved it. Couldn’t put this one down, though the prose did leave me with mixed feelings. And I hated literally every single character. Still. Couldn’t put it down. How’s that for a trip?

- The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: What an absolutely devious book. Ishiguro creates a stunningly heartbreaking narrator who is perhaps one of the most delightfully unreliable narrators I’ve read since The Good Soldier. The entire book is his effort to confront his own memories as the begin to hit him in later life, and to threaten to unravel everything he thought he knew about his beloved employer and about his own station in life. The narrator seems unable to admit fault in himself and in his employer because, if he does, it means he too was a part of one of humanity’s greatest evils. Really brilliantly conceptualized and intimately rendered. The story itself is, well, not exciting, and I think some people will have a hard time getting through it because of that. It doesn’t seem like much happens, and ultimately what the reader might hope or expect of the narrator does not come to fruition. It’s not, in that sense, a satisfying read. But what a concept, and what effect.

- *Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell: I bought this book on its release day over a year ago. I knew I’d like it. But for some reason, I put off reading it. Time passed. Reviewers raved about it. And I started to think, ‘Oh, but what if I don’t like it, after all?’ Did I hype it too much? Am I now going to be disappointed by a book I was sure I’d enjoy? So, there it sat on a shelf, neglected, while I read a thousand other things. Finally, this month, I sat down and gave myself a stern talking to: “Just read it! This isn’t life and death, man, it’s a book!” And now I’ve finished, and Hamnet was somehow everything I expected and nothing I expected. What a beautiful damn story this is, synthesizing biographical fiction, magical realism, and literary history. It is also not about Hamnet. It’s not even about Shakespeare. I mean, the guy is in it, of course, but the story is actually about… well… go read it and find out.

- *At Swim, Two Boys by Jamie O’Neill: Like Hamnet above, this one is a book I’ve been meaning to read since it was fist published (although in this case, I’m behind two decades instead of just a year.) If I’m remembering correctly, I tried to pick this one up years ago but put it away because its prose is a bit difficult to get into. I knew I’d stick with it this time, though, because this is the book that the Classics Club Spin pulled for me. I was hoping for it, I got it, and now I’ve read it. And what an absolute joy. That’s a strange thing to say about a book with such a heartbreaking conclusion, but the whole thing is a gorgeous experience. It did take me some time to settle into the prose, especially the dialogue, which is written in local dialect—a kind of Irish-English slang from the early 1900s. There’s plenty of erudite vocabulary in the straight exposition itself, which led me to thanking my dictionary app, but the dialogue (and one character’s inner-monologues, especially), took effort. At some point, though, I realized I had settled into the beautiful flow of things and had been invited in, much as the sea invites O’Neill’s two young protagonists into it. I don’t think I can recommend this one highly enough for any lover of historical fiction, gay fiction, and/or literary fiction. A remarkable achievement.

So, I had a wonderful time with poetry this month and will continue it (to a lesser extent, probably) next month. My two starred readings of the month, though, are At Swim, Two Boys and Hamnet, both of which are also two of my favorite books of the year. We’ll see how they hold up to the next 8 months of reading!

Oh, right! Here’s what I’ll be reading in May for AAPI Heritage Month: