Roof Beam Reader

Adam Burgess

Sunday Salon (1:2)

RBR Sunday Salon

Volume 1, Issue 2

Welcome to the second volume of Roof Beam Reader’s Sunday Salon!

Welcome to the second volume of Roof Beam Reader’s Sunday Salon!

This week, in addition to recapping my own posts and sharing what I’m currently reading, I’m sharing my favorite reads from my favorite bloggers, as well as a number of fascinating articles from across the web, including some on science, history, and politics. There’s also a provocative piece on how to organize one’s bookshelf that I would love to hear your thoughts on!

I hope you enjoy some of these as much as I did!

Blog Posts I Loved

- Bookish Byron: Brontë Dissertation. “After a lengthy period of racking my brains, trying to choose an interesting topic to write on, jumping from research solely based on Charlotte to the Byronic hero, I finally settled on exploring the relationship between marriage and class in Charlotte’s Shirley, Emily’s Wuthering Heights, and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.”

- Blogs of a Bookaholic: Why You Need to Read Only Love Can Break Your Heart. “Webber’s writing shines as bright as the desert stars she depicts and is as hopeful as the morning sunrise over the rocky sand. It’s also got an almost dreamy/surreal quality to it – this book sucks you in and the rest of the world fades away.”

- I Would Rather Be Reading: The Beautiful Tragedy of Jane Austen’s Final Novel. “As with all of her other works, Sanditon attracted supporters and detractors in equal measure. While many believed in its innovative style, critics such as E.M. Forster believed that Austen’s lingering illness and approaching death overshadowed the work itself.”

Literary Miscellany

- The Paris Review: Holy Disobedience: On Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal by Patti Smith. “Fourteen years later, Genet writes The Thief’s Journal, his most exquisite piece of autobiographical fiction. He is the transparent observer reclaiming the suffering and exhilaration of his own follies, trials, and evolution. There are no masks; there are veils. He does not retreat; he extracts the noble of the ignoble.”

- Lit Hub: In Defense of Keeping Books Spine-In. “Here’s a fundamental truth about my life as a writer and reader that might offend my fellow bibliophiles more than anything else I could possibly say: for over two years, I arranged all my books spine-in. I’ve gathered that this is a controversial declaration, and that I risk inciting upset, even outrage.”

History & Politics

- CNN: More Than 100 Newspapers will Publish Editorials Decrying Trump’s anti-Press Rhetoric. “The Boston Globe has been contacting newspaper editorial boards and proposing a “coordinated response” to President Trump’s escalating “enemy of the people” rhetoric.”

- The Paris Review: America’s First Female Mapmaker. “Willard is well-known to historians of the early republic as a pioneering educator, the founder of what is now called the Emma Willard School, in Troy, New York. But she was also a versatile writer, publisher and, yes, mapmaker. She used every tool available to teach young readers how to see history in creative new ways.”

Culture & Society

- My Modern Met: Guy Creatively Arranges His Massive Library of Books into Imaginative Scenes. “Bookstagrammer James Trevino uses his massive library of books for more than just reading. With a shelf arranged like a rainbow, he pulls from his collection and transforms the texts into imaginative displays.”

- The Fresno Bee: Humanities Are Becoming the Lost World of Education. “What’s missing here is the deepening and ripening of the mind that occurs when we study the humanities. What’s missing is the expansion of our vocabularies and imaginations. What’s missing is reflection on the meaning of life.”

Science, Tech., & Nature

- CNN: Parker Solar Probe Launched Sunday. “NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will explore the sun’s atmosphere in a mission that launched early Sunday. This is the agency’s first mission to the sun and its outermost atmosphere, the corona.”

- Strategy + Business: Gutenberg’s Revenge: Why Books are the Only Form of Physical Media whose Sales are Growing. “There’s another factor that continues to support the sale of physical books: the stubborn survival of booksellers, especially the independents that have endured a series of onslaughts.”

Teaching & Writing

- The Chronicle: The Rise of the Promotional Intellectual. “The main tasks of a professor are to teach and do research [. . . ] Now, it seems, a new task has been added to the job: promotion. We are urged to promote our classes, our departments, our colleges, our professional organizations . . . ourselves.” (This article may be restricted.)

- Prolifiko: How to Harness Your Writing Brain’s Hedonic Hotspots. “Writing is never going to be something you do on autopilot – it’s way too difficult for that. But there are some simple methodologies based in neuroscience you can use to make you, and your writing brain, feel more positive about finding a regular time.”

Posts from Roof Beam Reader

Currently Reading

- Good Without God by Greg M. Epstein

- So Big by Edna Ferber (for #CCSPIN)

All work found on roofbeamreader.com is copyright of the original author and cannot be borrowed, quoted, or reused in any fashion without the express, written permission of the author.

August Checkpoint! #TBR2018RBR

We’ve reached month eight in our TBR Pile Challenge, which means we are now in the final quarter of the event! (It also means, for me, fall semester begins in less than two weeks — where did the summer go!?) I hope you’re all enjoying the challenge, the monthly check-ins and questions, and any reading that you’re doing from your own lists; I have to admit, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by my own choices.

Last month, I challenged all of us to get 200 reviews written and linked-up with the Mister Linky widget below. It looks like we almost made it, so great job! We’re sitting at 193 at the moment.

Question of the Month: Have you challenged yourself with a genre outside of your “comfort zone” this year? Did you read non-fiction when you’re usually a fiction person? Try a collection of poetry when you normally prefer prose? A classic, when you prefer contemporary YA?

My Progress: 6 of 12 Completed / 5 of 12 Reviewed

I’ve read 6 of my books and am currently reading number 7. I’ve reviewed 5 so far (just need to get my thoughts down on Pudd’nhead Wilson!) As of last month, I was sitting at 4 books read and reviewed, so I am feeling pretty good about the progress I made in the last 30 days, and I hope I can continue to read these regularly so that I complete all 14 on my list by year’s end. Here’s hoping!

I’ve read 6 of my books and am currently reading number 7. I’ve reviewed 5 so far (just need to get my thoughts down on Pudd’nhead Wilson!) As of last month, I was sitting at 4 books read and reviewed, so I am feeling pretty good about the progress I made in the last 30 days, and I hope I can continue to read these regularly so that I complete all 14 on my list by year’s end. Here’s hoping!

Of course, with the new semester starting, most of my time goes back to prepping classes, grading papers, and doing the reading (re-reading) I need to do for my classes, especially the literature courses. I’ve got six novels to re-read this semester while teaching them, and they are all personal favorites (hooray!), but that said, it will take away from my own new/pleasure reading.

My completed reads:

- The Hound of the Baskervilles (Completed 1/3/18)

- Aristotle’s Poetics (Completed 1/10/18)

- Ready Player One by Ernest Cline (2011) (Completed 01/25/18)

- The Courage to Teach by Parker J. Palmer (Completed 03/10/18)

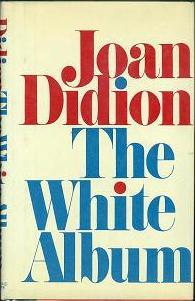

- The White Album by Joan Didion (Completed 08/04/18)

- Pudd’nhead Wilson by Mark Twain (Completed – Review to Come)

- Good without God by Greg M. Epstein (Currently Reading)

How are you doing?

Below, you’re going to find the infamous Mr. Linky widget. If you read and review any challenge books this month, please link-up on the widget below. This Mr. Linky will be re-posted every month so that we can compile a large list of all that we’re reading and reviewing together this year. Each review that is linked-up on this widget throughout the year may also earn you entries into future related giveaways, so don’t forget to keep this updated! At the end of the challenge, all entries will go into one big raffle for the $50 book prize!

MINI-CHALLENGE #3 WINNER

Congratulations to Jean at Howling Frog Books, whose comment last month was randomly drawn as the winner of Mini-Challenge #3. She will receive a book of her choice, up to $20USD, from The Book Depository.

LINK UP YOUR REVIEWS

Author Spotlight: Irving Stone

Every so often, a Twitter thread or Facebook meme or “Top Ten Tuesday” type survey will come around, asking people to share “a book you think everyone should read” or an “under-rated author people should try.” And every time this happens, I almost always recommend the same writer, Irving Stone, and one of two of his books, which happen to be personal favorites, LUST FOR LIFE and THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY.

Every so often, a Twitter thread or Facebook meme or “Top Ten Tuesday” type survey will come around, asking people to share “a book you think everyone should read” or an “under-rated author people should try.” And every time this happens, I almost always recommend the same writer, Irving Stone, and one of two of his books, which happen to be personal favorites, LUST FOR LIFE and THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY.

So, when a Twitter thread recently posed the question a bit differently (“which book/author have you stopped recommending?”) It gave me pause. I realized that, yes, I have slowly but surely begun to recommend Irving Stone less and less because, for some reason, people just refuse to read him.

To counteract my negligence, I have decided to put together a spotlight piece on Irving Stone. I hope that you will get to know him, a bit, and begin to understand why I think he’s worth reading. Maybe some of you will even give him a try!

IRVING STONE (1903-1986)

Irving Stone was a California writer best known for his biographical novels, a genre which owes its contemporary form largely to Stone’s first novel of “bio-history,” Lust for Life (Evory, 642). In these works, Stone would “novelize accounts of real people, based on meticulous research” (NNDB). His first biographical novel, a great success, was followed by other notable works in the same genre, including Love is Eternal: A Novel of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln (1954) and The Agony and the Ecstasy: A Biographical Novel of Michelangelo (1961).

Irving Stone was a California writer best known for his biographical novels, a genre which owes its contemporary form largely to Stone’s first novel of “bio-history,” Lust for Life (Evory, 642). In these works, Stone would “novelize accounts of real people, based on meticulous research” (NNDB). His first biographical novel, a great success, was followed by other notable works in the same genre, including Love is Eternal: A Novel of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln (1954) and The Agony and the Ecstasy: A Biographical Novel of Michelangelo (1961).

Stone was born Irving Tennenbaum on July 14, 1903, in San Francisco, California. In 1934 he married his long-time editor, Jean Factor, and they had two children together. According to Stone, he began reading at a very early age, and onward through life, which caused him to be given the nickname “bookworm” (Sarkissian, 361). As a boy growing up in San Francisco in the early 1900s, Stone bore witness to many momentous events, including the great earthquake of 1906, the World’s Fair of 1914, and the implementation of Prohibition in 1919 (Sarkissian, 362-4). When Stone was not yet in high school, his mother (who was uneducated but who “craved books and knowledge”) brought him to the University of California at Berkeley and demanded with “a burning intensity” that he promise “that no matter what happens” he attend that school (364).

Stone kept that promise, thanks in large part to several fortuitous instances of luck (and evasion). For example, when he moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles, the registrar at his new school, Manual Arts High School, mistook “English and Composition” for two separate courses; this led to young Irving – a not great student in general—being awarded not eight units of As in “English and Composition” but sixteen units of As, eight each for the two separate subjects, which were not actually separate. The registrar asked Stone to confirm this, and he did. It was only much later in life that he admitted the deception (Sarkissian, 366).

Another fortunate event took place after his first semester at the University of Southern California (USC), where Stone enrolled because he had missed the deadline for Berkeley’s spring registration. Stone, quite sure of his inability to successfully complete courses in mathematics and the sciences, learned upon enrolling at Berkeley that they had enacted a new policy requiring two years of study in these very subjects (he had gotten through them in high school only because he had friends and classmates willing to do his work for him). Luckily for Stone, an exception was written into the rules whereby any incoming student with at least 14 credits of university coursework could waive the math and science requirements. Stone had completed exactly that many hours at USC, in anticipation of his eventual transfer to Berkeley (366).

Another fortunate event took place after his first semester at the University of Southern California (USC), where Stone enrolled because he had missed the deadline for Berkeley’s spring registration. Stone, quite sure of his inability to successfully complete courses in mathematics and the sciences, learned upon enrolling at Berkeley that they had enacted a new policy requiring two years of study in these very subjects (he had gotten through them in high school only because he had friends and classmates willing to do his work for him). Luckily for Stone, an exception was written into the rules whereby any incoming student with at least 14 credits of university coursework could waive the math and science requirements. Stone had completed exactly that many hours at USC, in anticipation of his eventual transfer to Berkeley (366).

So, Stone’s rise out of the lower classes and through academia is, by his own admission, largely due to certain circumstances of fortune, but also to his own abilities as a writer. Ultimately, honored his mother’s wishes by studying Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned his B.A. in 1923. He then earned his M.A. from the University of Southern California in 1924 (Evory, 641).

From boyhood and through his university years, Stone worked odd jobs, including as a vaudeville musician, a milk depot employee, a delivery boy, and an usher (Sarkissian, 364-5). According to Stone, even before his fifteenth birthday he was working up to thirty-five hours a week, while going to school (365). This would have been possible –even probable—considering Stone’s family’s lack of income as well as the fact that child labor laws in the United States were not yet in effect until 1938. It is possible that much of this early experience would feed his later academic and professional interests, including his search for “the wellsprings of human conduct” and his particular interest in “social economics” including “labor relations, poverty controls, slum clearance, and the like” (Sarkissian, 368). In college, Stone “supported himself by playing saxophone in a dance band” (Krebs) and was also granted teaching fellowships at USC and at Berkeley (Sarkissian, 368).

After finishing college and graduate studies, Stone “supported himself by writing detective stories” and a few plays. It was only after being rejected 17 times that Lust for Life, his first success, was finally accepted for publication (Britannica). Stone was particularly interested in representing, honestly, the overlooked or the misunderstood – the underdogs of history. As Albin Krebs puts it, “what aroused Mr. Stone’s curiosity was the suspicion that a character had been misunderstood or unfairly misrepresented by previous studies” (para. 15). For this reason, he often wrote about “totally unimportant figures” (Sarkissian, 370) such as Clarence Darrow, or misunderstood (particularly by the American audience) personalities, such as Vincent van Gogh and Michelangelo. In addition, Stone –again possibly due to the influence of his childhood, and especially the formative influence of his mother – “was also intrigued by how the women in the lives of men in the public eye influenced them” (Krebs, para. 15). This interest resulted in a tetralogy of popular novels, three of which, according to Stone, were about “women [who] had been traduced and vilified by history” (Sarkissian, 370).

After finishing college and graduate studies, Stone “supported himself by writing detective stories” and a few plays. It was only after being rejected 17 times that Lust for Life, his first success, was finally accepted for publication (Britannica). Stone was particularly interested in representing, honestly, the overlooked or the misunderstood – the underdogs of history. As Albin Krebs puts it, “what aroused Mr. Stone’s curiosity was the suspicion that a character had been misunderstood or unfairly misrepresented by previous studies” (para. 15). For this reason, he often wrote about “totally unimportant figures” (Sarkissian, 370) such as Clarence Darrow, or misunderstood (particularly by the American audience) personalities, such as Vincent van Gogh and Michelangelo. In addition, Stone –again possibly due to the influence of his childhood, and especially the formative influence of his mother – “was also intrigued by how the women in the lives of men in the public eye influenced them” (Krebs, para. 15). This interest resulted in a tetralogy of popular novels, three of which, according to Stone, were about “women [who] had been traduced and vilified by history” (Sarkissian, 370).

In crafting his novels, what was most important to Stone was that the history informing his stories be as factually accurate and as detailed as possible, which takes a great amount of time and effort when one is writing about actual, historical figures. In his prologue to The Irving Stone Reader, he writes, “the biographical novelist must be the master of his material; the craftsman who is not in control of his tools will have his story run away with him” (19). Stone’s extensive and exhaustive research into his subjects led him and his wife to numerous countries, including a lengthy stay in Italy, where Stone spent years researching the life of Michelangelo. In addition to this, the pair spent two years living in Vienna, researching Sigmund Freud, and later moved to Greece to research the lives of Henry and Sophia Schliemann (Sarkissian 376).

Stone’s research did not simply lead to the completion of his novels, however; indeed, much of his work on these historical figures often resulted in other contributions to academia, such as bringing “much previously unpublished and important information into print,” including Freud’s papers and Michelangelo’s and Van Gogh’s letters (Evory, 643). Stone has also received numerous awards, including the Christopher Award and Silver Spur Award (1957), the Golden Lily of Florence, Rupert Hughes Award, Gold Medal from Council of American Artist Societies, Gold Trophy from American Women in Radio, Corpus Litterarum Award from Friends of the Libraries, University of California, Irvine (Evory, 641), and the John P. McGovern Award (NNDB). He also founded the Academy of American Poets in 1962 (Britannica).

Finally, although Stone withdrew from his Ph.D. program at Berkeley prior to completing his dissertation, he did eventually receive an honorary Doctorate of Laws from Berkeley, as well as honorary doctorates from A&H University, California State Colleges, Coe College, Hebrew Union College, and the University of Southern California (OAC).

Works Cited

- Contemporary Authors: Autobiography Series. Vol. 3. Ed. Adele Sarkissian. Detroit: Gale, 1986.

- Contemporary Authors: New Revision Series. Vol. 1. Ed. Ann Evory. Detroit: Gale, 1981.

- “Finding Aid to the Irving Stone Papers.” Online Archive of California. The Regents of the

- University of California, 2009.

- “Irving Stone.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013.

- “Irving Stone.” Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League, 2013.

- “Irving Stone.” Fantastic Fiction. Fantastic Fiction, 2013.

- “Irving Stone.” NNDB. Soylent Communications, 2013.

- “Irving Stone.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia, 2013.

- “Irving Stone, Author of ‘Lust for Life,’ Dies at 86.” Obituaries. New York Times, 2013.

- Stone, Irving. The Irving Stone Reader. Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1963.

All work found on roofbeamreader.com is copyright of the original author and cannot be borrowed, quoted, or reused in any fashion without the express, written permission of the author.

RBR Sunday Salon (1:1)

RBR Sunday Salon

Volume 1, Issue 1

Welcome to the first edition of Roof Beam Reader’s Sunday Salon! This new weekly feature was inspired by the many “critical linking” and “weekly round-up” type posts that a number of my favorite book bloggers do so well. I’ve been weighing whether or not to jump-in with my own version of this for some time, now.

Welcome to the first edition of Roof Beam Reader’s Sunday Salon! This new weekly feature was inspired by the many “critical linking” and “weekly round-up” type posts that a number of my favorite book bloggers do so well. I’ve been weighing whether or not to jump-in with my own version of this for some time, now.

I finally made the decision to move forward after realizing that, at the end of every single week, I have something like 18 browser windows open on my phone and/or desktop, stuck on posts that I loved and want to re-read or share. So, why not create a shareable archive of my own, where everyone gets the benefit of what I think constitutes “good and important reading,” and where I can find again in some easy, logically organized way?

As you’ll see, I have a number of genres/categories, each with a few favorite links from things I read in that category during the current week (they might have been published earlier, but I only just got around to reading them myself during the current week.) I hope you enjoy some of these as much as I did!

Blog Posts I Loved

- On Bookes: “The Birthday of the Infanta by Oscar Wilde.” . . . I began to really appreciate what a powerful writer he was. That, I believe, is confirmed in his short stories: there is great beauty, darkness, and melancholy in his stories that never fails to leave an impression.

- The Book Binder’s Daughter: “The Worst Kind of Irreligion: George Eliot on the Reception of Daniel Deronda.” In a letter dated the 29th of October, 1876, she describes . . . her surprise that Daniel Deronda has not met with more resistance because of its Jewish subject matter. She describes the shameful racism and bigotry she witnesses among her own class…

- The Misfortune of Knowing: “We March(ed).” With every attempt to suppress voters, every reiteration of Trump’s unconstitutional Muslim Travel Ban, every mean-spirited version of TrumpCare, every attempt to strip our right to enforce civil rights laws through litigation, and every roll back of our environmental protection policies, my disdain for Donald Trump and the GOP at every level of government intensifies.

Noteworthy Literary News

- JSTOR Daily: “When Harriet Beecher Stowe and George Eliot Were Penpals.” On April 15th, 1869, the famous American novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote a letter from her home in Mandarin, Florida, to the famous British novelist George Eliot. Thus began a long, fascinating, passionate, epistolary friendship between these two very different writers.

- BBC: “The 100 Stories that Shaped the World.” In April, BBC Culture polled experts around the world to nominate up to five fictional stories they felt had shaped mindsets or influenced history. We received answers from 108 authors, academics, journalists, critics and translators in 35 countries…

- Literary Hub: “25 Nonfiction Books for Anger and Action.” For those looking to channel their fear and grief into anger and action, here are 25 books which help illustrate exactly what’s at stake under the new administration and demystify how you can—and why you should—resist.

History and Politics

- The Stranger: “The Green Party, Ladies and Gentlemen.” There are lots of examples out there of Republicans running as Greens or recruiting homeless people to run as Greens or financing the campaigns of Green Party candidates at the local and national level. Republicans donate to Greens, Republicans run as Greens, and useful-to-the-GOP idiots vote for Greens.

- BBC: “Forbidden Love: The WW2 Letters Between Two Men.” While on military training during World War Two, Gilbert Bradley was in love. He exchanged hundreds of letters with his sweetheart – who merely signed with the initial “G”. But more than 70 years later, it was discovered that G stood for Gordon, and Gilbert had been in love with a man.

Culture and Society

- The New Yorker: “A Hollywood Hedonist turns Ninety-Five.” Scotty Bowers is one of the dirtiest nonagenarians you’re likely to come across. He’s also a Hollywood legend of sorts.

- Conde Nast Traveler: “14 Best Coffee Shops in Chicago.” Chicago takes its coffee seriously. With independent roasters and cafes as numerous in certain neighborhoods as bars.

Fascinating Miscellany

- The New Yorker: “The Many Lives of Pauli Murray.” A poet, writer, activist, labor organizer, legal theorist, and Episcopal priest, Murray palled around in her youth with Langston Hughes, joined James Baldwin at the MacDowell Colony the first year it admitted African-Americans, maintained a twenty-three-year friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt, and helped Betty Friedan found the National Organization for Women.

- The New Yorker: “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds.” Coming from a group of academics in the nineteen-seventies, the contention that people can’t think straight was shocking. It isn’t any longer. Thousands of subsequent experiments have confirmed (and elaborated on) this finding.

Essays and Articles on Writing

- Medium: “Hello, Go Away.” Writers bravely put their work out into the world and someone who supposedly knows the industry is saying, “I don’t want it.” But undesirable though the message may be, isn’t a direct response better than silence?

- The Rumpus: “Why Writing Matters in the Age of Despair.” That was the narrative we spun about who we were. It was a better story than the one we were actually living. It turns out you can live in a fiction for a long time. For a lifetime, perhaps, but my limit was twelve years.

Posts from Roof Beam Reader

- “Joansing for Didion.” Reading Joan Didion is like reading the 4th of July. It is fireworks in my brain and sitting down with an old friend to chat about and think about everything and nothing, and leaving exhausted by the pure and exhilarating experience of being together again.

- “Considering the Secret of Northanger Abbey.” Neill refers to each character individually, pointing out their less admirable traits, without paying much attention to what positivity or sensibility the characters might actually bring to the story.

- “Prompt: The Sound of Your Language – Be Gorgeous.” The exercise in general was enjoyable. It reminds me of reading like a writer. The sound and rhythm are important…

Currently Reading

- Good Without God by Greg M. Epstein

- Sometime After Midnight by L. Philips

All work found on roofbeamreader.com is copyright of the original author and cannot be borrowed, quoted, or reused in any fashion without the express, written permission of the author.

“Joansing” for Didion

While Halloween has always held a coveted spot in my heart and imagination, the truth is, I used to get almost as excited for the 4thof July. It was like the summertime version of my favorite autumn day, where the rules were bent and the pure joy of living was the day’s entire purpose. I distinctly remember people from my childhood commenting about my love for this holiday, and about how patriotic I must have been. But that was never the reality.

While Halloween has always held a coveted spot in my heart and imagination, the truth is, I used to get almost as excited for the 4thof July. It was like the summertime version of my favorite autumn day, where the rules were bent and the pure joy of living was the day’s entire purpose. I distinctly remember people from my childhood commenting about my love for this holiday, and about how patriotic I must have been. But that was never the reality.

What I loved were the barbecues and the being outside with friends all day, playing kickball and having water balloon fights, and getting so bloated on hot dogs and ice cream that I thought I’d burst before the big city fireworks show. I loved the morning parade, being in it as a Boy Scout and, when Boy Scout days were over, arising early to save the family seats along the sidewalk, close enough to grab candy and other goodies from the parade participants.

And I can still hear the sound of the ice cream truck, softly in the distance. I can see my friends’ faces as they heard it too; we’d look at each other at just the right moment, realizing it was time to pause the game, rush home to beg for a dollar, and then get back out into the street in time to stop the truck as he came tinkling down the road. But more than anything, it was the fireworks.

Reading Joan Didion is like reading the 4th of July. It is fireworks in my brain and sitting down with an old friend to chat about and think about everything and nothing, and leaving exhausted by the pure and exhilarating experience of being together again. There’s no special magic to fireworks, once you learn they’re little more than powder, a match, and some cleverly timed fuses. In the same way, one can “figure out” the technical and creative style of Didion in order to explain just how she does what she does, and why it is so compelling. But even now, that knowledge, about fireworks and Didion, remains subliminal, and I continue to be, above all, caught up in the spectacle, in the color and rhythm and choreography of it all.

The White Album is a collection of essays written in the “aftermaths of the 1960s.” Her subject matter ranges from personalities like Doris Lessing to events like the Manson murders. What holds it all together is the skeptical and, in hindsight, sobering but accurate perspective of an often-mistaken view about the United States’ “greatest decade.” Didion takes an unflinching look at the optimism of the 1960s, the supposed freedoms, and the many breakdowns and reckonings of that idealism, the unmasking, as it were, of one decade by its disillusioned successor, the 1970s.

In the first essay, from which the collection takes its title, Didion writes, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live . . . we look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” In other words, the writer’s work at this time was to try to make sense of the senseless, and the 1970s more than any other time revealed that, sometimes, the narrative is simply wrong.

In later essays, she writes about architecture, like governors’ mansions and museums, as signifiers of our culture’s shaken and superficial, even misleading, view of our own past. In “The Getty,” for example, she writes, “the Getty tells us that the past was perhaps different from the way we like to perceive it.” If the collection has one unifying theme, it is this critique on what we Americans think we know about our own past, and how quickly truth and reality seem to slip through our fingers. To read this collection now, in 2018, is a particularly painful and humbling experience.

One of the most under-rated essays in the collection is its last, “Quiet Days in Malibu.” In a way, this piece, written between 1976-1978, is the logical concluding piece not just because it comes near the end chronologically, but because Didion writes about the personal experience of living in Malibu in order to reveal that it, too—the reality of her hometown—is different from how it is perceived by those who live outside of it. Malibu, California has an aura about it that relates to nothing real, according to Didion, just as the 1970s exposed the truth of the 1960s, puncturing its aura forever. Aptly, and somewhat ironically, at the center of her experience in this essay is an immigrant who runs a local flower shop for decades. His are some of the most expensive, sought-after plants in the world and, like everything else, their position is precarious. Danger and uncertainty, instability and tragedy, are always lurking. And yet, so is hope—inexplicable, untraceable, blind hope.

I adore Didion’s writing, so beware my bias. That said, this is perhaps her most tightly themed collection. Despite an essay or two with which I had some intellectual or emotional disagreement (there is one titled “The Women’s Movement” that left me feeling more than conflicted), I felt a fierce and powerful sense of grounded awe while reading these essays and after finishing the collection. This is what I’ve come to expect, personally, from my time with Joan Didion.

The rocket’s red glare. The bombs bursting in air.

This was the fifth book read for my TBR Pile Challenge.

All work found on roofbeamreader.com is copyright of the original author and cannot be borrowed, quoted, or reused in any fashion without the express, written permission of the author.